A Man,A Can,A Plan

Michael Zimmer founded the Sardine Museum and Herring Hall of Fame to preserve a chapter of Grand Manan history as much to celebrate its striking aesthetic. When he died in 2008, he left it to Nancy Ross, a young woman from the island. Now it is up to her and Grand Manan to determine what will become of his gift.

Photos by Peter Cunningham

The playful, flat-bottomed aluminum vessel is at once utterly of the rugged island in the Bay of Fundy and altogether a reflection of the character of the monied eccentric who founded a creative history project in a clutch of smokehouses in a hardcore fishing village remote even by the standards of an island that can only be reached by an hour-and-a-half ferry ride.

Zimmer's obituary in the New York Times on Nov. 2, 2008, calls him a memory-keeper, "the man who guarded and exhibited what the islanders threw away," describing the Sardine Museum and Herring Hall of Fame as his last great project, "a poetic environment, part museum, part curiosity cabinet, part living memory."

Now Zimmer has given it back to the island. The next few years will reveal what Grand Manan makes of his quirky gift.

On an early July day when the sun is winning a pitched battle with the fog, Dawson Brown is at the Sardine Museum, smoking fillets of herring he caught the day before in Dark Harbour.

The inside of the smokehouse feels partly like a barn, partly like a temple, light shafts flooding through open upper shutters , highlighting furls of smoke twisting up into the dark wooden rafters where generations of Grand Mananers made a living, turning the perishable bounty of the sea into a preserved commodity that was shipped around the world. Zimmer called the smoke a "visible and olfactory sign of money ."

Now, nearly two years after his death, telltale grey threads are once again fingering out of the old buildings. The wispy plumes aren't as thick as they once were, when practically every man, woman and child in Seal Cove worked in the sardine industry, when Grand Manan, at its height, produced 80 per cent of the world's supply of smoked herring, a million 10- or 18-pound boxes a year in its heyday.

Still, the smoke is a sign that a tradition that just a decade ago seemed destined to utter extinction persists, however precariously.

Dawson is well versed in the history of the trade, and of the sea. A fisherman's vocabulary rolls off the 10-year-old's tongue as he talks naturally of seines and weirs, hogsheads and scale baskets.

It's in his blood.

His grandfather, Kenny, remembers working in the sardine industry all summer long when he was Dawson's age.

"I think the first job I had was to build these boxes" he says, holding a small wooden crate.

"And then you'd go from there when you were old enough to dipping from the tanks to the table for the women to string ... when you were strong enough, you'd wheel the carts from the stringing shed to the smoke shed."

Kenny demonstrates how the men would straddle the beams, passing strung herring sticks up to those bestriding higher ones until the rafters were filled with sticks of fish.

Dawson and his friend, Michael Brown (no relation), are building a 10-foot-cubed smoking shed in Dawson's backyard.

"I wish they'd start these things up again," Michael says, looking up in the shed that still carries the scent of generations of old smoke and fish oil.

Michael Johannes der Baptist Karl Maximilian Heinrich Hugo Zimmer was a man of delicious contradictions: an architect who only ever built a couple of houses, a wealthy sophisticate of hardy cultural intellectual stock who saw art in a herring stick; an urbanite who made the pages of Vogue and other glossies who lived off the grid in his youth; a cosmopolite who was just as happy trading tales with old lobster men as with the bon vivants who peopled his cort�ge in the city.

Michael Zimmer was born in Heidelberg in 1934.

In 1939, his family fled Nazi Germany to New York where his father, a Sanskrit scholar and Indologist, taught at Columbia, and the Zimmer home became a hub for intellectuals from Europe and America.

A keen student, Michael Zimmer won the Harvard architecture prize in 1956, but his architecture career was short lived, by choice.

Instead, he and his first wife, Emily Harding, a niece of Brooke Astor, left New York to live in the Caribbean.

In 'Where Have All the Eccentrics Gone?' a 2008 column on Forbes.com, Melik Kaylan describes Zimmer as a "grand personage in his heyday, a handsome, careless, mysteriously melancholy Beau Brummel figure from the 1960s and '70s" whose friends knew him "as a flashing raconteur and boulevardier."

Filmmaker Vera Graaf met Zimmer in the early '70s after encountering a friend from Paris who was staying with Zimmer's mother. "He said, 'You must meet this fascinating old lady,' " Graaf says from Long Island.

While Christiane Zimmer hosted a salon of sorts for artists and thinkers, it was her youngest son who most interested Graaf. "I decided that Michael was too fascinating to let go," she says.

They were together for 16 years, living in New York and St. Barts at Le Camp, a collection of little huts on a piece of sand and palm trees by the sea.

The green compound was "a playful laboratory for his ideas of the good life, guided by aesthetic principles," Zimmer's obituary states, "a meticulously choreographed piece of theatre which Michael directed, smoking, talking, always a glass of rum in hand..."

Zimmer was a "tremendous eccentric, who lived preposterously, and experimentally - and this is the point," Kaylan wrote.

"He'd lived his life like the aesthetes of Wilde's time, his life was his art, and that was enough."

Zimmer financed his lifestyle with family money. In the late '60s he sold Yo Picasso, a Picasso self-portrait that was a family heirloom. In 1989 it went for $47.9 million at Sotheby's, then the second-highest amount ever paid for an artwork at auction.

Royalties from Zimmer's maternal grandfather, the famed Austrian poet and librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, who wrote the book for several Strauss operas, including Elektra, also kept the Le Camp and, later, the Sardine Museum afloat.

"Every time anyone produced the Rosenkavalier anywhere in the world, his bank account went 'ka-ching,' as he put it," Kaylan wrote.

While Zimmer enjoyed financial security from his family's success, his sense of accomplishment, his faith that his projects, including the museum, were worthwhile, was less stable.

In Stranger From Away, a 24-minute documentary film Graaf and Max Scott made about the Sardine Museum in 2003, Zimmer reflected on what his ancestors might think of his venture on Grand Manan.

"Grandfather probably wouldn't really approve," he says. "Mother is rolling in her resting place. 'For this we sent the boy to Harvard!' "

Michael Zimmer first visited Grand Manan in the mid-'90s. He had followed his wife at the time, a Frenchwoman named Veronique Sari, who was looking for whales. But it was herring - and the fish's associated architecture - that caught his eye.

"Michael, never having been an avid whale-watcher, got bored pretty quickly and sat on the shore and started looking around and saw Seal Cove and fell in love with it," Graaf says.

A building and design enthusiast, Zimmer's gaze fell upon a compound of defunct smokehouses next to the bay. The herring sheds, once the social and economic hub of the island, were shuttered.

"I think the idea of the island's history, and it just sort of disappearing under an avalanche of new and quote-unquote modern things, that made him sad," Graaf says, "so he decided to do something about it, and he combined his love of architecture with his sense of preservation."

Zimmer's brand of conservation must have struck some local old-timers as curious.

Not a re-enactment, the museum reflects an interest in objects more aesthetic than archival. Zimmer gave former utilitarian objects a second life, making them his own in the process

"He didn't hold on to the past here," Peter Cunningham, a New York photographer with deep roots on Grand Manan, says. "He was transforming the past."

He couldn't help it, Graaf says. "He may have set out to preserve, but what he really did was tell his own tale. And that was always injected with a hefty dose of Zimmer-esque details."

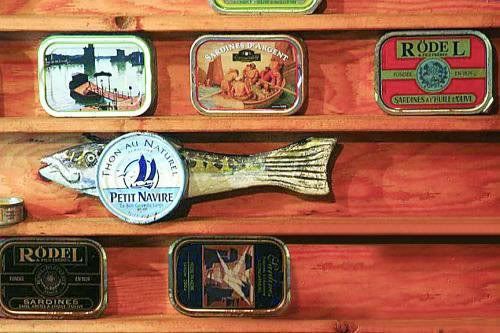

Those details leaned towards repetition in form and line and objects in multiples, a sensibility that show itself throughout the museum's several buildings. In the upstairs of the smokehouse, the space between wall studs is filled with empty cat food cans, the empty silver rounds making a pleasing pattern.

In a den looking over the lawn and cove beyond, diagonal lines of the round butts of herring sticks alternate with circles filled with corkscrews to create a textured wall surface.

"That's Michael Zimmer right there. It's the details, and it's all over these sheds," Cunningham says. "It's Michael's arrangement of things. We're always trying to keep up with Michael."

"He was what the French call a bricoleur - he always did something," Graaf says. "He would lay out things, make drawings, have plans. Everything had to be pleasing to the eye, everything had to be beautiful. And his sense of beauty wasn't necessarily everyone else's sense of beauty. It was in part very utilitarian, it was very quote-unquote modern, it was shaped by the time when he studied architecture."

In the summer, Zimmer invited artists from New York and elsewhere to come to the museum for residencies, using local materials to make sculptures and collages. The outside of one red shed is painted with a geometric silver pattern that looks 3-D from a certain angle. In another, behind stacks of lobster traps stored for the off-season, is a paint-splattered installation of herring sticks arranged in radiating circles and herringbone lines.

The museum was a mix of high culture and low, a place where visitors and locals mingled in Zimmer's rustic quarters, sitting around the wood stove, sharing a drink or a meal and stories, always stories.

Peter Cunningham met Michael Zimmer on the ferry to Blacks Harbour following Zimmer's first visit to Grand Manan.

"I didn't know who he was, he was just a New Yorker who wanted to buy the sheds," he says.

The photographer, who got his start shooting Bruce Springsteen in New York in the mid-'70s, has been coming to Grand Manan all his life and shooting it for years, a "participant observer" of life there. "This place has resonance with me."

Neighbours in the city, Cunningham and Zimmer became friends. In New York, they would go for grilled sardines at Chez Jacqueline in Greenwich Village. When they met on Grand Manan, Cunningham would visit the museum, camera often in hand, and they would swap tales and information about the island.

"I quickly grew to see that Michael was learning very quickly about the island and soon he was teaching me things I didn't know," Cunningham says. "Some of the subtleties of the culture here, he was able to articulate them."

Cunningham, for his part, was able to share insights gleaned from decades on Grand Manan. At their first meeting, on the ferry, he told Zimmer, "There should be a sign, 'All ye who enter here abandon hope,' because I've seen so many dreams dashed on this island. People come with very high hopes," he says, but they don't always get the support they hope for.

Zimmer wasn't immune to this disappointment. '"At one point he said he felt he had an audience of one," Cunningham says.

But that may have been Zimmer's cynical side talking. While he felt a deep connection the museum, and to Seal Cove, always planning events and improvements for the next year, he could be negative when he was away from it, Graaf says.

" 'I'll never go back to Grand Manan and this is ridiculous and what am I doing there?' " he'd say to her. "That was typical Michael."

While the museum had its frustrations. "He had a vision of what he wanted to do - which he did," Cunningham says.

Zimmer saw himself as a guardian in the interim between the obsolescence of the old sardine industry and a time when the smokehouse and its associated artifacts would be valued.

"No Grand Mananer would keep it," Zimmer had said.

But in the end that is exactly who he left it to.

Nancy Ross is not an artist or archivist, but the Seal Cove native knows all about the Sardine Museum.

"I was here from the beginning of it all," she says, her husky voice inflected with the down east accent of the island.

Ross was 12 or 13 when the smokehouses shut down. Before that, she worked in them. "That was my first job when I was 10," she says, "stringin' and bonin'."

When Zimmer died in October 2008, he left the museum to her.

"It's just that I appreciate it and I'm not going to sell it for storage," she says.

She first met Zimmer when he hired her as a teen to do odd jobs around the compound.

"I painted all of it 20 million times," she says.

For a girl from Seal Cove, the interesting tribe that had always followed Zimmer - including to Grand Manan - was a revelation to Ross.

"It was really cool," she says. "It was its own little community."

Zimmer's Grand Manan entourage included a chef from the Caribbean who made his room in the attic for warmth, and would wear wool sweaters even on "hot" days when locals were down to light summer togs.

Ross remembers seeing dreadlocks for the first time on the head of one of Zimmer's crew. "That's something that you never see here, ever," she says.

The late Tony 'The Fish' Nunziata was a from-away regular who spent many a summer on Grand Manan as the Sardine Museum's director before his death in July 2009. A Greenwich Village actor and composer with a past so storied people often doubted the veracity of his tales until they were proven true, he shared Zimmer's passion for the place, and its famous product.

"A sardine is not a sardine is not a sardine," Nunziata tells a tour group at the museum in one of a series of YouTube videos demonstrating the depth of his knowledge as he educates visitors on the herring industry from sea to smokehouse to shipping. "They're really pretty amazing. I love them."

Of course, at the centre of it all was Zimmer himself.

"He was rich," Ross says, "but he walked around here filthy, with bare feet."

Now Ross, the only female truck driver on the route between Grand Manan and New England, delivers seafood to some of the same wholesalers who once bought Grand Manan sardines by the case.

She juggles her job with running the museum, spending as much time there as she can.

"I would love to come and stay here all summer," she says.

She uses her own money to keep the museum going. It has no outside financiers, save government funding to hire Valerie Mallock, a local high school student, for the summer.

"My job title is half a mile long," Mallock quips as she passes over a card identifying her as seasonal director/manager of Seal Cove Seawall National Historic Site.

Ross is trying to figure out how to keep the museum afloat. Admission is free and contributions are meagre.

"Hopefully we'll have enough donations to keep the lights on," she says.

Graaf will visit Grand Manan later this week, to see the museum and encourage Ross.

"Nancy could have let that museum go," Graaf says. "She had her chance to say, 'Good-bye museum, I don't want to be bothered.' She scratched together the taxes. She made it. Nancy is amazing. She has a full-time job, she just wants to do it."

On Canada Day, Nancy Ross donned a jaunty white sailor's cap and took Zimmer's sardine can boat out on the water as part of the celebrations at Seal Cove.

While some islanders, including members of her family, don't see the value in the museum, she shares Zimmer's conviction it's worth saving.

"The sad part, for people from here, it's not really old enough to be appreciated," she says.

"It's kind of in-between right now. Those guys don't know it," she says, gesturing towards Mallock and another teen, "and the old folks forget it."

For those whose memories are intact, and they are legion, "they still remember it as work."

That said, locals are starting to donate objects, such as wooden buoys. And when Ross asked some older islanders who used to work in the smokehouse if they'd like to come for a day of boning and smoking the response was keen.

"I think people are beginning to care more," Cunningham says. "The sense I get is that people here are starting to feel the spirit of the museum more."

He says there's something "genius" in Zimmer leaving it to a local. "He gave it to Nancy Ross because, in my view, he wanted to give it back to the island. Now it's up to the island."

While Ross figures out how to organize and fund the museum, she continues the guardianship Zimmer began, keeping the buildings maintained and the objects intact in one place, artfully arranged.

"I can hear him in my head," Ross, who once spent the better part of an afternoon arranging a series of rustic wooden forms to Zimmer's satisfaction, says. She is trying to honour his vision - although she's no artist.

"All we can do now is keep it alive," Cunningham says.

"But I built it, too," Ross says. "It's part of me."

Michael Zimmer

Sticks of smoked herring

The late Tony Nunziata is the former director of the Sardine Museum and Herring Hall of Fame. He was a member of the tribe of interesting people who followed Michael Zimmer on his adventures, including to Grand Manan.

7

Michael Zimmers aesthetic taste leaned towards repetion,and objects in multiples

Kate Wallace covMichael Zimmers aesthetic taste leaned towards repetion,and objects in multiplesers the arts for the Telegraph-Journal. She can be reached at wallace.kate@telegraphjournal.com .

Michael Zimmers outside a shed painted with a geometric silver design that looks like 3-D from certain angles. It was designed by a New York Artist.

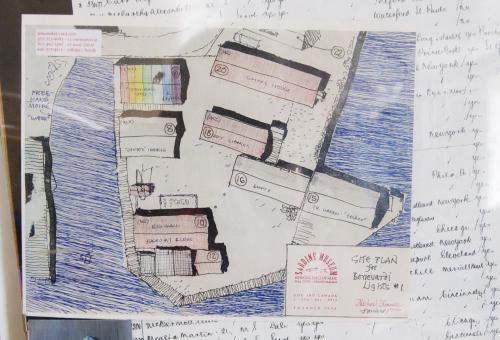

Michael Zimmer's sketches and plans for the museum

Seal Cove Native Nancy Ross started working at the Sardine Museum as a girl.Whem Zimmer died in October 2008 he left it to her." I appreciate it and I am not going to sell it for storage, " she says

The distinct aesthetic of the smokehouses appealed to Zimmer,who studied architecture at Haravard in the 50's

Sticks of smoked herring

Kate Wallace covers the arts for the Telegraph-Journal. She can be reached at wallace.kate@telegraphjournal.com . Photos by Peter Cunningham.